Tuesday, February 28, 2006

the beach

Friday, February 24, 2006

work (2)

Drawing number two in progress.

I think what I liked about this drawing was the way that the blank paper became a space that enabled conversation —a kind of arena for thoughts. What is depicted in the drawing approaches Chantal Mouffe’s definition of the political, the friend/enemy distinction (see below, February 22nd) … So you might say that the drawing concerns the political, rather than politics. Even though the work itself doesn’t arrive at a final definition or concrete representation of the concept.

In this case, the conversation revolved around the concepts of ‘we’, ‘us’, ‘them’, ‘you’ … and the difficulty of defining these concepts in relation to politics in general, and to the current situation in the Netherlands in particular.

Each work seems to point me towards creating more and more elaborate guidelines for the participants, to start the process with i.e. an overview of what I see as the distinction between politics and the political, and the story of my thinking around the idea. But this assumes that this dynamic of friend/enemy, us/them, citizen/not-citizen is an aspect of everyone’s social and political awareness – and not something that needs to be further discussed, of discovered and further defined through each successive encounter.

If I begin with this definition I feel that I will be determining the outcome. But isn’t the way that I begin the drawing already creating this distinction? As I set the process up, seating someone opposite me across the table? And this unfamiliar situation of making a drawing with someone, me, more or less an unknown quality – is this situation of knowing/not knowing analogous to the friend/enemy relationship?

Labels: studies for the shape of government, the netherlands

Thursday, February 23, 2006

(no title)

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

Work

I began work on [one] of my projects here yesterday. Many thanks to Niels, the first volunteer.

Like allot of the things that I do, and, I guess, allot of the things that every artist does, it isn't always apparent to me why I am doing what I'm doing. The thing that I like about his project is that making the work is a process of finding out what the work is. It generates more questions every time.

The project has a fairly simple basis. I ask people to make a drawing with me of how they think government works. I provide the paper and the other materials. We sit on either of the long sides of the paper. We start with a conversation about how they think government works. The drawing is a representation of that conversation, with both of us making contributions to the drawing.

The result is a representation of subjective knowledge, but also a representation of the conversation, and representation of the communication that occurs between myself and the other artist. So in a sense it is "about" government, and in another sense it’s not about government at all.

this is a familiar image of debate between our Prime Minister (seated, on the left hand side) and our Opposition Leader (standing, on the right) in the Australian parliament

The first unanswered question is whether I want to challenge this idea, or entrench the idea further.

The second question comes from some of the people I have approached to be part of the project - am I a political artist? No, and um ... yes. In a sense (he says in an enthusiastic rush, wildly making connections between thoughts that no-one else can follow) every artist is political and every artwork is political. It's always been a feeling that I've had, that if we participate in something (like the art world, or capitalism, or the tax system) we implicitly give our consent to the way that something is organised, we agree with it in a sense. Chantal Mouffe puts it quite succinctly in an interview about the connections between art and politics ... she says

... One cannot make a distinction between political art and non-political art because every form of artistic practice either contributes to the reproduction of the given common sense —and in that sense is political— or contributes to the deconstruction or critique of it. Every form of art has a political dimension.

... but I guess that I'm getting ahead of myself here. Because the interview begins with Mouffe making a distinction between 'politics' and 'the political' —

What I call "the political" is the dimension of antagonism—the friend/enemy distinction. And [...] this can emerge out of any kind of relation. It's not something that can be localised precisely; it's an ever-present possibility. What I call "politics", on the other hand, is the ensemble of discourses and practices, institutional or even artistic practices, that contribute to and reproduce a certain order. These are always in conditions that are potentially conflictual because they are informed by, or traversed by, the dimension of "the political." [ ...]

I want to continue and say how I think that this relates to the drawing project, but I have also just realised that the "we" that I keep talking about and the audience that the interview assumes are people that have a choice whether to be part of a country, a system of government, or a way of life. Maybe I'll just leave that hanging there, as a problem that is internal to this project, and by implication the discourse that the project is part of.

I was going to say that the drawing project is an attempt to make material some of the ideas that jumped out at me when I read this interview the first few times, i.e.: the distinction between "politics" and "the political", the dimension of antagonism that is present in every relation, and that artistic practices contribute to and reproduce a certain order.

Anyway the Chantal Mouffe interview is available in a journal called "Grey Room", It's called Every form of Art has a Political Dimension and it is in Issue 02, Winter 2001 - it's available on-line, but you have to subscribe, which is why I haven't linked to it.

The third question that remains unanswered is -why am I only asking artists to participate? There are many long conversations to be had about this. (One involves the issue of involving (non-art) people in artistic practice, and a kind of discussion about something that I want to call ethics but probably has another name - and deserves to be pursued at length, perhaps as a topic for a MA research project, so if I ever do a Masters ...)

I know for sure that while I am continually drawn to work with other people, I also find it really difficult to get to know people - artists are the easiest people for me to work with because we at least have something to start the conversation. The other answer is that the project is in response to the current interest in the (one of many) art world(s) in political practice - I was interested in how much artists actually knew about the system that they were commenting on ... that, making a comment on "politics" or "the political" seemed to me to assume a position of being already outside the system, and, like many of contemporary art's excursions (into "the everyday" for example), the political was treated as someplace else. It assumes that artists or institutions have a position outside the political, when really our world, the art world, is a microcosm or intensification of the politics that exist out there. It is also inextricably linked to the world of politics through the provision of government funding, the stucture of institutions, and our education system - however, sometimes artists dealing with the political can be kind of like civilising missionaries or anthropologists.

So another signpost, here, from an interview with Lucy Suchman - an anthropologist who I first heard interviewed on the radio about her work studying the behaviour of people interacting with office machines (photocopiers, faxes, printers). Such a topic piqued my interest - and I looked her up. I have held onto this interview because it points to some of the ways that I feel about making work with other artists and about the art world. The full transcript I have, more than ever, a sense of the immovability of these institutions is at http://www.dialogonleadership.org/interviewSuchman.html

Lucy Suchman: (…) I was also very much interested in Native Americans, as many students of anthropology are. I was just overwhelmed by the sense of their wonderful ways of organizing and relating to the world. But it was a very terrible history, and I started to feel that the last thing that Native Americans needed was another anthropologist studying them. I thought instead I should study the institutions that were closer to my own position in life and that had tremendous consequences for Native Americans, for example, the Bureau of Indian Affairs. This was also at the time when the idea of studying up, as it was called in anthropology, was developing at Berkeley.

Interviewer: “Studying up” means?

Lucy Suchman: Anthropology had traditionally been concerned with non-industrial cultures, or those that major Western societies were interested in administering and dominating, and that’s carried over into the field. Even within American anthropology, the focus has always been on Native Americans, and then more recently on various minority groups within the United States, rather than on mainstream, middle-class Americans, on elite institutions, powerful organizations. In the 70s there was an initiative within anthropology that said: We have as much culture here as anywhere else. In fact, we have a responsibility to turn the anthropological gaze back on ourselves, and really understand ourselves as participants and co-creators of the world, rather than just as observers.

Like allot of the things that I do, and, I guess, allot of the things that every artist does, it isn't always apparent to me why I am doing what I'm doing. The thing that I like about his project is that making the work is a process of finding out what the work is. It generates more questions every time.

The project has a fairly simple basis. I ask people to make a drawing with me of how they think government works. I provide the paper and the other materials. We sit on either of the long sides of the paper. We start with a conversation about how they think government works. The drawing is a representation of that conversation, with both of us making contributions to the drawing.

The result is a representation of subjective knowledge, but also a representation of the conversation, and representation of the communication that occurs between myself and the other artist. So in a sense it is "about" government, and in another sense it’s not about government at all.

To start with, I think that I am already creating a representation of an aspect of government by having the other artist sit across the table from me, and then creating something through what is [more or less, depending on the person] a process of consensus. This is an idealised and simplified representation of consensus decision-making and of the process of government.

this is a familiar image of debate between our Prime Minister (seated, on the left hand side) and our Opposition Leader (standing, on the right) in the Australian parliament

The first unanswered question is whether I want to challenge this idea, or entrench the idea further.

The second question comes from some of the people I have approached to be part of the project - am I a political artist? No, and um ... yes. In a sense (he says in an enthusiastic rush, wildly making connections between thoughts that no-one else can follow) every artist is political and every artwork is political. It's always been a feeling that I've had, that if we participate in something (like the art world, or capitalism, or the tax system) we implicitly give our consent to the way that something is organised, we agree with it in a sense. Chantal Mouffe puts it quite succinctly in an interview about the connections between art and politics ... she says

... One cannot make a distinction between political art and non-political art because every form of artistic practice either contributes to the reproduction of the given common sense —and in that sense is political— or contributes to the deconstruction or critique of it. Every form of art has a political dimension.

... but I guess that I'm getting ahead of myself here. Because the interview begins with Mouffe making a distinction between 'politics' and 'the political' —

What I call "the political" is the dimension of antagonism—the friend/enemy distinction. And [...] this can emerge out of any kind of relation. It's not something that can be localised precisely; it's an ever-present possibility. What I call "politics", on the other hand, is the ensemble of discourses and practices, institutional or even artistic practices, that contribute to and reproduce a certain order. These are always in conditions that are potentially conflictual because they are informed by, or traversed by, the dimension of "the political." [ ...]

I want to continue and say how I think that this relates to the drawing project, but I have also just realised that the "we" that I keep talking about and the audience that the interview assumes are people that have a choice whether to be part of a country, a system of government, or a way of life. Maybe I'll just leave that hanging there, as a problem that is internal to this project, and by implication the discourse that the project is part of.

I was going to say that the drawing project is an attempt to make material some of the ideas that jumped out at me when I read this interview the first few times, i.e.: the distinction between "politics" and "the political", the dimension of antagonism that is present in every relation, and that artistic practices contribute to and reproduce a certain order.

Anyway the Chantal Mouffe interview is available in a journal called "Grey Room", It's called Every form of Art has a Political Dimension and it is in Issue 02, Winter 2001 - it's available on-line, but you have to subscribe, which is why I haven't linked to it.

The third question that remains unanswered is -why am I only asking artists to participate? There are many long conversations to be had about this. (One involves the issue of involving (non-art) people in artistic practice, and a kind of discussion about something that I want to call ethics but probably has another name - and deserves to be pursued at length, perhaps as a topic for a MA research project, so if I ever do a Masters ...)

I know for sure that while I am continually drawn to work with other people, I also find it really difficult to get to know people - artists are the easiest people for me to work with because we at least have something to start the conversation. The other answer is that the project is in response to the current interest in the (one of many) art world(s) in political practice - I was interested in how much artists actually knew about the system that they were commenting on ... that, making a comment on "politics" or "the political" seemed to me to assume a position of being already outside the system, and, like many of contemporary art's excursions (into "the everyday" for example), the political was treated as someplace else. It assumes that artists or institutions have a position outside the political, when really our world, the art world, is a microcosm or intensification of the politics that exist out there. It is also inextricably linked to the world of politics through the provision of government funding, the stucture of institutions, and our education system - however, sometimes artists dealing with the political can be kind of like civilising missionaries or anthropologists.

So another signpost, here, from an interview with Lucy Suchman - an anthropologist who I first heard interviewed on the radio about her work studying the behaviour of people interacting with office machines (photocopiers, faxes, printers). Such a topic piqued my interest - and I looked her up. I have held onto this interview because it points to some of the ways that I feel about making work with other artists and about the art world. The full transcript I have, more than ever, a sense of the immovability of these institutions is at http://www.dialogonleadership.org/interviewSuchman.html

Lucy Suchman: (…) I was also very much interested in Native Americans, as many students of anthropology are. I was just overwhelmed by the sense of their wonderful ways of organizing and relating to the world. But it was a very terrible history, and I started to feel that the last thing that Native Americans needed was another anthropologist studying them. I thought instead I should study the institutions that were closer to my own position in life and that had tremendous consequences for Native Americans, for example, the Bureau of Indian Affairs. This was also at the time when the idea of studying up, as it was called in anthropology, was developing at Berkeley.

Interviewer: “Studying up” means?

Lucy Suchman: Anthropology had traditionally been concerned with non-industrial cultures, or those that major Western societies were interested in administering and dominating, and that’s carried over into the field. Even within American anthropology, the focus has always been on Native Americans, and then more recently on various minority groups within the United States, rather than on mainstream, middle-class Americans, on elite institutions, powerful organizations. In the 70s there was an initiative within anthropology that said: We have as much culture here as anywhere else. In fact, we have a responsibility to turn the anthropological gaze back on ourselves, and really understand ourselves as participants and co-creators of the world, rather than just as observers.

Labels: studies for the shape of government, the netherlands

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

On looking at looking

Ann Stephen's biography of Ian Burn, launched in Melbourne recently. Ann also co-ordinated, along with Luke Parker, a series of page works for an online publication, Natural Selection Magazine, in response to the statement by Ian Burn -

“What is held up as originality is a myth, given the degree to

which art evolves as a collective enterprise, with artists always

building on other artists’ work... To talk to other artists’ work,

and simultaneously to talk about the other artists’ work...

Isn’t that what constitutes originality anyway?”

— Ian Burn in conversation with Imants Tillers 1993

The page works can be found in section 25/ page 84 of the magazine.

Monday, February 20, 2006

coat

The blog has been slow work. To remedy this, I'm going to include a few things from emails, so there will be a bit of time travel over the next few days ...

from a mail to my father on Sunday -

I have finally bought a coat. I was lucky that I asked the sales woman whether the green coat I was trying on looked to big on me (for some reason all Dutch coats are too wide across the shoulders) and she said yes, and started to suggest different options. It is usually OK to ask a sales-person's advice in shops - because the response is almost always honest. In the end, I found a grey duffle coat, which is, by some strange co-incidence an Australian brand, and it fits well, and is very warm. So my walks in the morning are now especially nice.

I have noticed that it is a matter of etiquette here to eat toasted sandwiches with a knife and fork. It's something that I generally ignore, but when, the other day, I ordered a sandwich on 'stokbrood' (stick bread, a baguette) it turned out to be an open sandwich and I had to struggle through the experience with my knife and fork. It was worth it and I was hungry. I find this a small but somehow significant point of difference between Australian and Dutch culture - that it is generally 'not done' to eat with one's hands (especially when sitting at a table, but hot chips also come with a small plastic fork ...), whereas in Australian culture there is a whole array of things to eat with one's hands. Whether you follow this or not seems to be an indication of your class, or even your "Dutchness".

I have also learnt over the last few weeks not to take the Dutch manner of speaking always in the imperative to heart. My friend Annelys notes that the Dutch are known throughout Europe for giving unsolicited advice. So a conversation runs something like a series of statements and commands - which is different from the english mode of conversation which is has many more questions and is more open ended. I also have to take into account that the conversation is being conducted usually in someone's second, third or forth language. ...Something that I have been reflecting on is the world's increasing 'proficiency' with English. I find here that English is the language of commerce, business and trade - and this is reflected in the way that it is used. So I often feel I get the wrong impression of people's character and motives - that they are merely interested in the opportunity that I might offer.

I have started to read a novel by a Dutch author from den Haag, Louis Couperus. The novel is called called Inevitable, and it was published in 1900. It would probably compare well with Henry James - if I had got that far in my reading. Even though it is in translation, I can hear the difference in the way that it is written, again, a series of statements, confident and precise. Ewoud says that he is one of the 'greats' in Netherlands literature & admired for his use of language, style & wit.

There are now many responses to the email that we sent out asking people to participate in my collaborative drawing project. I have met two of them and will start making drawings this week. I spent a lovely few hours with an Israeli/Dutch woman in her studio discussing her work and also talking about living in the Netherlands. She spoke about being in Israel as a feeling of not belonging in a particular community (one parent was a Sephardic Jew, the other Ashkenazi). Afterward, I was thinking about the Netherlands being the place where it is possible to be in this in-between state ... it is indeed a place full of people who are either physically or spiritually or culturally stateless. Although the Netherlands, like so many other places in the world, is increasingly less welcoming to people who find themselves inclined or forced to leave their country of birth - more anxious about it's borders and 'national identity'.

Another point of reflection has been a statement by American philosopher Stanley Cavell concerning America - that it is a fiction, a home that everyone imagines, but which no-one ever really arrives at. It is always unapproachable. (Emerson's phrase from his essay "Experience" ... I feel a new heart beating with the love of the new beauty. I am ready to die out of nature and be born again into this new yet unapproachable America I have found in the West...) I think that, during the 20th Century, many places were like America - places of new beginning for people who were dissatisfied or displaced - Australia, Canada, the Netherlands ... but this period of migration and optimism seems to be truly historical now. Countries are fortresses, not places of the imagination, not questions about what it means to belong to a place.

Sunday, February 19, 2006

world esperanto association

Friday, February 17, 2006

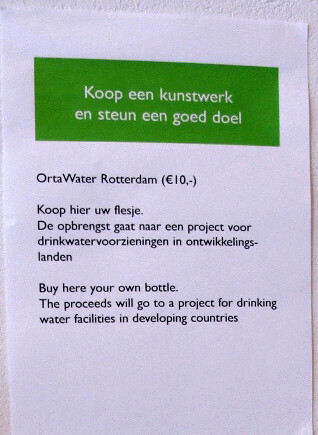

buy an art work and support a good aim

The machine translation of the text in Dutch at the top of this sign is buy an art work and support a good aim ... It's from the Lucy & Jorge Orta show at Boijmans - here,

The show finished on the 5th of February, but I have been thinking about this show for a few weeks now and trying to figure out why it bugged me so much. My first thoughts were that the show is an expression of a kind of anxiety that art institutions have, and that artists have, about the relevance of their practise. In the face of problems like the lack of clean drinking water in the third world, contemporary art and it’s institutions can seem fairly irrelevant. But I ask myself all the time whether this feeling of … irrelevance, or helplessness, or impotence … can be addressed by taking ‘an issue’ as the subject of the work that you make.

My second thoughts were that the problems of the third world are pretty much related to the development of capitalism, so it seems a little short sighted to try and remedy these problems by selling something in a museum. The idea that you can alleviate the effects of capitalism by buying more things, instead of attempting to modify your own behaviour. The installation doesn’t address the distribution of funds raised by the sale of the bottles of water. For example, what are the museum’s administration costs, and how much does it cost to produce the bottles? What are the costs of sending the money out of the country?

Related to this was something I heard on the radio a few months ago about the environmental cost of building or renovating a home or a new building. The information I remember is that the environmental cost of carpeting a floor of a building was equivalent to filling the same space with water 10 times. That’s just the cost in water, you can add all the other raw materials, electricity etc on to that. So, what’s the environmental cost of producing a single bottle made from clear glass? Is this equivalent to filling the bottle ten times over and then emptying it down the drain? What is the environmental footprint of a contemporary art exhibition?

The show finished on the 5th of February, but I have been thinking about this show for a few weeks now and trying to figure out why it bugged me so much. My first thoughts were that the show is an expression of a kind of anxiety that art institutions have, and that artists have, about the relevance of their practise. In the face of problems like the lack of clean drinking water in the third world, contemporary art and it’s institutions can seem fairly irrelevant. But I ask myself all the time whether this feeling of … irrelevance, or helplessness, or impotence … can be addressed by taking ‘an issue’ as the subject of the work that you make.

My second thoughts were that the problems of the third world are pretty much related to the development of capitalism, so it seems a little short sighted to try and remedy these problems by selling something in a museum. The idea that you can alleviate the effects of capitalism by buying more things, instead of attempting to modify your own behaviour. The installation doesn’t address the distribution of funds raised by the sale of the bottles of water. For example, what are the museum’s administration costs, and how much does it cost to produce the bottles? What are the costs of sending the money out of the country?

Related to this was something I heard on the radio a few months ago about the environmental cost of building or renovating a home or a new building. The information I remember is that the environmental cost of carpeting a floor of a building was equivalent to filling the same space with water 10 times. That’s just the cost in water, you can add all the other raw materials, electricity etc on to that. So, what’s the environmental cost of producing a single bottle made from clear glass? Is this equivalent to filling the bottle ten times over and then emptying it down the drain? What is the environmental footprint of a contemporary art exhibition?

Making work ‘about something’ doesn’t really avoid the fact that art is always about aesthetics. And isn’t aesthetics a set of rules or conventions about how things are done in a certain situation or context? Not so much a language game as a highly specialised form of charades? So we have highly developed conventions for making a work that explodes the white cube, or making work that addresses the separation between art and life, or making work that questions the differentiation between high and low culture, and making work that addresses the issue of “x” … we have conventions for challenging conventions.

Monday, February 06, 2006

lost

I am back just now from a long walk in the mist - following my street directory toward a bit of green on the map - a very civilised park and very beautiful on this damp and misty day. I walked further along the waterside, over the Erasmusbrug, which is my current marker for known territory in Rotterdam …

I’m thinking about a friend’s comment about travelling – that one of the things that they like is the absence of personal experience implicit to objects and sites … and that somehow with that absence comes a clarity of thought

When I walk about here I feel like a blind person - and it makes me realise - for good or not so good - that my sense of being at home (which is different from being in one's home) has allot to do with the familiar. So I am feeling or experiencing a sense of the uncanny. I’m not well versed in the debate around the term – but I do have a feeling that the word is usefully ambiguous, and is often used as a matter of convenience or politeness by critics or curators – as a means of abbreviating or avoiding complexity. Anyway, at the moment - It is a sense of being un-homed, which is not quite homesickness (yet) or loneliness, not quite. Part of this uncannyness is the awful suspicion that I have no centre or soul, no personality apart from that which is continually enforced through the feedback loop of the familiar.

Also on my mind is the rhetorical question put to me the other evening by my friend Annelys over a beer and a snack consisting of croquets on bread (a particularly unfamiliar form of Netherlands cuisine – these are basically a crumbed deep-fried bolus of ragout, served with buttered white bread; you squash the croquet onto the bread and then spread it with mustard and eat the result with a knife and fork) … the question, How can you be an artist if you don’t like change? ... I guess the extension of this is the question of how can you be an artist if you are not willing to unbecome yourself, to loose your bearings, get lost in the mist...

Part of me reacts against the idea that, as an artist, you are duty bound to actively seek out and experience disruption, the unfamiliar, or the unknown. It seems a little outmoded and romantic. But then, one of my favourite bits of writing at the moment is this, from Thoreau – in the chapter titled “The Village” in Walden

It is a surprising and memorable, as well as valuable experience, to be lost in the woods any time. Often in a snow-storm, even by day, one will come out upon a well-known road and yet find it impossible to tell which way leads to the village. Though he knows that he has travelled it a thousand times, he cannot recognize a feature in it, but it is as strange to him as if it were a road in Siberia. By night, of course, the perplexity is infinitely greater. In our most trivial walks, we are constantly, though unconsciously, steering like pilots by certain well-known beacons and headlands, and if we go beyond our usual course we still carry in our minds the bearing of some neighbouring cape; and not till we are completely lost, or turned round--for a man needs only to be turned round once with his eyes shut in this world to be lost--do we appreciate the vastness and strangeness of nature. Every man has to learn the points of compass again as often as he awakes, whether from sleep or any abstraction. Not till we are lost, in other words not till we have lost the world, do we begin to find ourselves, and realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations.

Which I think I should one day embroider in coloured silks and hang above my studio door.

Saturday, February 04, 2006

Thursday, February 02, 2006

back in the Netherlands after a 6 day absence in the UK. I visited Birmingham for a day to see a friend's exhibition at the international project space at the college for art and design. The image above is the only one I have of Birmingham, it's the view from the window of the bedroom where I stayed for one night. London was frustrating, hard, exhilarating and wonderful in equal measures. I spent so much time in trains, on train platforms and in train stations listening to a automated announcement personally apologising for the delay in one service or another ... and it seems that this is a point of genuine cultural difference between Australia and the UK ... How can a machine express regret? Perhaps it is an apology given in the same spirit as most other courtesies in England. Bland, automatic and meaningless. It has made me conscious of how painfully polite Australians are.

Despite my fixated and relentless interest in the quality and genuineness of customer service, I did manage to experience several good things -

One, an astoundingly good couple of beers and a meal in a 'gastro pub' somewhere near London Bridge Station - as part of the celebrations for my friend Kate's birthday;

Two, the pre-renaissance bits of the National Gallery's collection;

Three; tea in the Wallace Collection Cafe in Manchester Square with friends Nag and Sue;

Four, standing outside the Tate Modern in a freezing wind with an Australian friend who was wearing bright pink earmuffs as a few tiny, delicate snowflakes fell;

Five; seeing the Dan Flavin retrospective at the Hayward Gallery with my friend Lucy, who enabled me to appreciate work that I would have otherwise disregarded.

I guess what I found most interesting about the Dan Flavin's show was watching the people moving about in the space - and the way that the work activates the space as a kind of stage for human movement and interaction. It was also interesting to reflect on the idea that allot of artists only need one idea - for Dan Flavin, it was this thing with the fluorescent tubes, and how the tube is first used as a linear, two dimensional form, and then gradually becomes a barrier across a space. It made me think all kinds of things about light, and corners, and the relationship that these things have to the sacred or the sublime. And you can trace this back to the Constructivist trick of placing abstract works in the corner of the room, a place usually reserved for a religious icon, - or the constructivists generally replacing images or representations of the sacred with pure abstraction ... and the show makes this quite explicit, starting with some early 'icon' works and leading into the works dedicated to Tatlin.

the site for the show is ... here ... http://www.hayward.org.uk/flavin/retrospective.htm

Unfortunately, the strategy of having only one idea doesn't work to Rachel Whiteread's advantage ... the new work commissioned for the Turbine Hall, 'EMBANKMENT' is quite awfully hollow. And the pun is intended, awfully.

There is a link, or a lineage, between one thing and the other - between the works made by people like the Constuctivists who, I believe, or have been told, believed in something and the work made by Dan Flavin to "celebrate empty rooms" or by Rachel Whiteread to celebrate empty boxes. But that isn't really it, I don't have a problem with whatever it is that DF is celebrating - nothing, or something, or something that will remain wholly unkown to us - it is just that the idea of the work as a window to the sublime persists, and I (still) can't find anything in the work to replace it. And I'm afraid that, for me, the work is never just aout itself, it refers to something. So as much as I enjoy the work, its emptiness disturbs me.

What happens then, I feel, is that other agendas colonise the work. Famously, Abstract Expressionism became political during the Cold War as an expression of American "freedom". That's what I worried about as I watched people wandering about in RW's massive installation of (casts of the inside of) empty boxes. They were there for something (an experience of the sublime or the spectacular, perhaps) but after my days of wandering in amongst countless Londoners just struggling to survive, it really was a bread and circuses kind of affair ...